Desi Pubs – the untold stories of British-Indian publicans

Words by Naz Toorabally

T: @NAZTOORABALLY // IG: @NAZTOORABALLY

When a colleague told me that a friend of a friend was writing a book on desi pubs, I was excited to hear that someone was writing a whole book on the topic. South Asian contributions to British culture aren’t document or celebrated nearly as much as they should be, and here was a book being published that would contribute to addressing this.

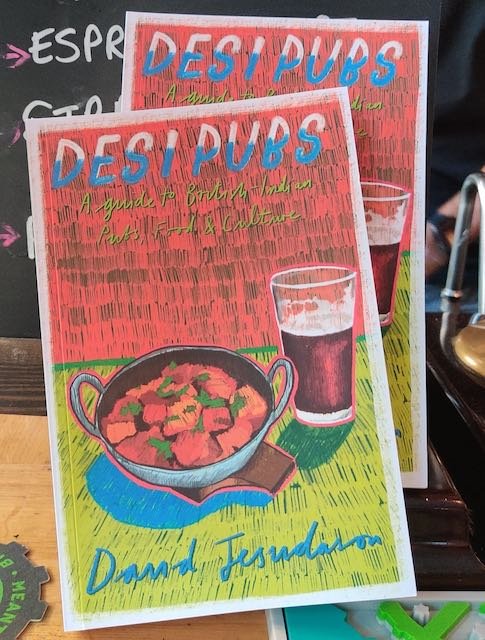

I soon found out that friend of a friend was journalist and beer writer David Jesudason, and the book in question was aptly entitled Desi Pubs: A guide to British-Indian pubs, food and culture. David and I chatted about his (then upcoming) book over the phone last month and he kindly invited me to his book launch event at desi pub the Gladstone Arms (or the Glad to locals) which I attended earlier this month.

A desi pub is a pub that is run by an Indian landlord, often Punjabi or Gujrati, and serves Indian food such as curry and grills or “mixies” as David puts it, as well as beer and other drinks you’d expect at your local pub. While food plays a huge part in their success, there’s so much more to these pubs that people should know. “I think when I set out this book, I wanted to change the default of what a landlord is exactly. But actually, that was very simple and easy to do,” says David. “What I discovered more was the social cohesion aspects of it. And like, I think the history of it is really important because they were set up because of the colour bar.”

Desi pubs were first established in the 1960s to fight against the colour bar operating in pubs which forced people of colour to drink in separate rooms from white people or even refused service altogether. This discriminatory practise wasn’t made illegal until the introduction of the Race Relations Act of 1965. Anti-racist protesters, including those from the Indian Workers’ Association, subsequently gave evidence against landlords that continued this discriminatory practise when their licenses came up for renewal, leading them to, rightfully, lose their licenses. As racist pubs closed down, it made way for Indian landlords to take over the leases and create a space whereby everyone could be served. By the 1970s, desi pubs became widespread in the Midlands, serving everyone from foundry and factory workers to football fans.

With its rich history, these stories were almost relegated to a chapter in a book about pubs when David originally pitched it. Too often South Asian stories that don’t fit the stereotypes of what people think it means to be South Asian aren’t given the platforms they deserve. Many publishers are too afraid to take a chance on stories they consider to be too niche or unsure of how to market. It’s a fact that the book’s managing editor, Alan Murphy, candidly discussed this at the launch event, owning up to his own reservations before the book was given the green light, with no resistance, by CAMRA. David speaks about desi pubs with such fervour, and it was listening to him argue his case that quickly convinced Alan that these stories of resistance, community and multiculturalism needed and deserved their own book.

I realised afterwards the importance of [desi pubs] and how empowering [they were] and how I could be myself in these spaces, so I started visiting some more.

Writing a book like this is also very personal, and during our conversation David’s own story reminded me of myself and others from the diaspora who have felt awkward by our lack of knowledge on Indian culture. David grew up in a small market town in Bedfordshire and being the only person of colour at his school, he learnt to tolerate the daily racism he faced, whether that was microaggressions or outright violence. His first pub visit was in the 90s when he was just 15 years old and it was no different: “I walked [into the pub] and one of the guys shouted “taxi” when he saw me because the only kind of representation they [had] of brown people or Asian people were taxi drivers.”

David’s father is Indian and born in Singapore and his mother is Malay, but he grew up feeling disconnected from his Asian heritage. “I kind of really suppressed all my Asian identity. Now, I say suppressed it, but my parents didn't really give me any… apart from food,” he explains. When David later went to university in Uxbridge, London – an area with a relatively large South Asian population – he says that “there were a lot of desis there and I didn't have any confidence around them.” Many children of immigrants have the shared experience of our parents wanting us to fit in and, whether intentional or not, for some of us that includes our parents not passing on languages or traditions to us. At the time, not only did David not know much about his culture, but he was also one of those weird Asian kids who “liked rock music a lot and anything guitar-based” which further alienated him from his peers, although discovering South Asian-led bands like Cornershop and Asian Dub Foundation was a turning point for him.

Discovering desi pubs was where David finally felt seen as a British Asian person and could feel completely as ease. “I didn't know what a desi pub was, never heard the term,” says David of his first desi pub visit, The Blue Eyed Maid on Borough High Street, which sadly shut down during the pandemic. “I realised afterwards the importance of it and how empowering it was and how I could be myself in these spaces, so I started visiting some more. The Scotsman in Southall was a big eye opener for me with the old uncles at the bar.”

David travelled to desi pubs around the UK, interviewing landlords about their pubs and the stories behind them for Desi Pubs. The majority of pubs featured in the book are, unsurprisingly, in London and the Midlands, but there are also a handful from the South and North of England, with one desi pub in Glasgow, Scotland. David tells me that the book was hard to put together as the landlords aren’t used to receiving interview requests, with some asking how much it would cost to be interviewed for the book. Further, the landlords are often very busy and don’t have a PR team to field these requests like a pub chain would. “I interviewed say 60 landlords in my book and they finally get to tell their stories,” says David. “I think when people get to read it, the effort that I put into it, compared to other beer books, they'll realise that this really isn't about pubs.” Indeed, Desi Pubs is more than simply a guidebook; it tells the story of resistance underpinning the existence of these pubs and the landlords running them, with their names and stories immortalised in print.

I think it's about time we realise how India changed Britain because we're always looking at how we've been changed by Britain, but let's look at it the other way round and look [at] the great things the diaspora has done in this country.

One pub featured in the book with important history is the Blue Gates Hotel in Smethwick. It was visited by US civil rights activist Malcolm X in 1965, following an invite from Avtar Singh Jouhl of the Indian Workers’ Association during protests against the colour bar. Upon visiting the Blue Gates, Malcolm X experienced the colour bar in action, saying the racism was “worse than America. Worse than Harlem”. Today the pub welcomes all and is noted in the book as the “official boozer” for West Bromwich Albion fans.

Crucial to the success of many of these desi pubs is their food. Many desi pubs want to create more than “pub food”. Some are a desi spin on traditional British pub grub like the Glad in London who have a mouth-watering Sunday roast menu and others like the Soho Tavern champion fusion cuisine – they’re famous for their chilli chips and their chilli sauces are so popular that they’re planning to sell a bottled range. Although these pubs are thriving, David emphasises how it’s not been easy weathering a pandemic and cost of living crisis. For example, the cost of vegetable oil increased by almost 50% between April and September in 2022. “[The landlords] might have put their prices up once or maybe twice, but they're absorbing all the rising costs.”

David Jesudason (left) being interviewed by Mark Machado

Desi Pale Ale by Meantime Brewing Company

At the book launch event held in London, the room was filled with people from all walks of life and was attended by some of the people who were involved in the book including Jagwant Johal, the son of Avtar Singh Jouhl. The evening kicked off with a relaxed and informative conversation between David and broadcaster Mark Machado, followed by delicious canapés served by the Glad. Meantime Brewing Company also brewed a beer especially for the launch of the book called ‘Desi Pale Ale’. I don’t drink alcohol, so I couldn’t appreciate the thought that had gone into this pale ale, but my partner is a fan of pale ale and loved it. We got to hear from the woman who made it – yes, she’s Indian for anyone wondering – and hearing her speak with such excitement over her creation made me wish I did like the taste of pale ale. It was while she was explaining the process behind her creation that she mentioned Ishaan Puri of White Rhino Brewing Co. (India's first craft brewer) who helped her into the industry – who also happened to be the friend of my colleague who helped get this book on my radar.

Desi Pubs is a wonderfully written book sharing previously untold stories of community and resistance, highlighting some beautiful examples of how Indian culture has impacted traditional (read: white) British culture. “I think it's about time we realise how India changed Britain because we're always looking at how we've been changed by Britain, but let's look at it the other way round and look [at] the great things the diaspora has done in this country,” says David and I couldn’t agree more.

Desi Pubs by David Jesudason is out now. Buy a copy and make your way around some of the UK’s best desi pubs.

Follow David on Instagram, Twitter and subscribe to his newsletter on Substack.

With thanks to Ella Patenall for transcribing the interview and sampling the pale ale.

About Naz

Naz Toorabally is a queer, British Indo-Mauritian musician, model and zine maker based in north London. She is the founder of WEIRDO Zine and fronts post-punk band Dogviolet. When she’s not making music or zines, you’ll find Naz hanging out with her cat.